![A giant concrete arrow on the abandoned Ashley Walk Bombing Range in the New Forest]() (Image: Mike Searle; giant arrow the abandoned Ashley Walk Bombing Range)

(Image: Mike Searle; giant arrow the abandoned Ashley Walk Bombing Range)

The New Forest is one of the most unspoiled natural wildernesses in South East England, one of the country’s most heavily populated regions. Its serene heathland, rolling pastures and verdant forests are a haven for wildlife and those seeking a quiet escape from the bustle of urban life. But the area wasn’t always so peaceful. Even today, reminders of its secretive wartime history endure half-concealed amid the landscape.

![Abandoned World War Two target structures on the Ashley Walk Bombing Range in the New Forest]() (Image: Mike Searle; remains of the wartime ship target)

(Image: Mike Searle; remains of the wartime ship target)

It was here that the Ashley Walk Bombing Range was established in the summer of 1940 under the control of RAF Boscombe Down, home of the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment (A&AEE). The aim was to develop, test and evaluate a new generation of British bombs that would carry to fight to the German heartland. Work called for a series of dummy installations to be constructed across the range, including a giant concrete arrow to direct incoming aircraft to an illuminated target in the valley at Lay Gutter, to the south.

![Abandoned World War Two target structures on the Ashley Walk Bombing Range in the New Forest 2]() (Image: Mike Searle; foundations of the demolished North Tower)

(Image: Mike Searle; foundations of the demolished North Tower)

Explaining Ashley Walk’s background, the Real New Forest Guide writes: “At the start of World War Two, British bomb technology had not really progressed a great deal since the end of the Great War in 1918 when a 20lb bomb was considered large. Against this background there was an arms race to catch up with the perceived superiority of the German Luftwaffe and the weaponry that they had at their disposal. As a result, over the next five years this tranquil part of the New Forest would have more armaments dropped on it… than most other parts of England, with the exception of the larger cities – and included the largest ever bomb to be dropped on British soil.”

![Map of Ashley Walk Bombing Range in the New Forest]() (Image: Mike Searle; map of Ashley Walk Bombing Range)

(Image: Mike Searle; map of Ashley Walk Bombing Range)

Construction of the range began after the New Forest Verderers – tasked with stewarding the area’s common land and royal forests – approved an application to make 5,000 acres available to the Air Ministry for munitions testing. In the process, three houses were evacuated and nine miles of security fencing installed. Thirteen gates allowed access to authorised personnel, some of whom were billeted in huts opposite the Fighting Cocks pub in Godshill.

![Abandoned World War Two target structures on the Ashley Walk Bombing Range in the New Forest 5]() (Image: Mike Searle; an abandoned concrete arrow near the North Tower site)

(Image: Mike Searle; an abandoned concrete arrow near the North Tower site)

Locals discussed developments on Ashley Walk Bombing Range among themselves in hushed voices. But on the whole, the general public knew little of the secretive work underway within, despite reports of local children using the range as a playground. In fact, much of the clandestine research and development conducted at Ashley Walk remained shrouded in mystery until the latter decades of the 20th century. Even so, the surviving infrastructure scattered across the wild heathland tells the story of an important chapter in British military history, and the crucial role it played in the development of hard-hitting ballistics technology.

![Abandoned World War Two target structures on the Ashley Walk Bombing Range in the New Forest 3]() (Image: Mike Searle; site of the Main Practice Tower)

(Image: Mike Searle; site of the Main Practice Tower)

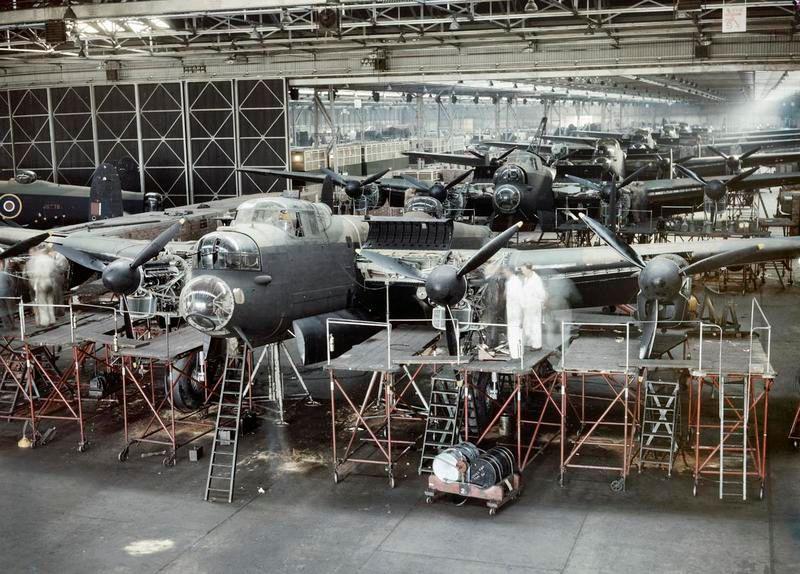

According to Aircraft & Airshows: “…every type of air dropped ordnance used by the RAF (with the exception of incendiary weapons) was tested here between 1940 and 1946. Along with the air dropped ordnance, guns and rockets were also tested and evaluated. The types of bombs tested ranged from small anti-personnel types to the ultimate in air dropped ordnance, the 22,000 lb Grand Slam earthquake bomb.”

![Abandoned World War Two target structures on the Ashley Walk Bombing Range in the New Forest 4]() (Image: Mike Searle; N/S range indicator on the abandoned New Forest bombing range)

(Image: Mike Searle; N/S range indicator on the abandoned New Forest bombing range)

Ashley Walk Bombing Range was broken into two sections. A smaller practice range with a diameter of 2,000 yards allowed inert bombs to be dropped from a height of 14,000 feet. A diesel generator was on hand to illuminate targets during night bombing, and a control structure known as the Main Practice Tower oversaw operations from its vantage point on Hampton Ridge, close to the concrete directional arrow that hides on the heath to this day.

![Surviving observation near Amberwood in the New Forest echoes the abandoned Ashley Walk Bombing Range]() (Image: Jim Champion; surviving observation tower near Amberwood)

(Image: Jim Champion; surviving observation tower near Amberwood)

To the north, a larger 4,000-yard-diameter section of Ashley Walk, controlled by the North Tower, comprised the High Explosive Range where more powerful weaponry could be dropped from 20,000 feet up. A range office oversaw all operations, and two observation huts (one of which survives today) were also constructed. Two small airstrips near Godshill were built for transport purposes.

![Bomb crater near Leaden Hall on the old Ashley Walk Bombing Range]() (Image: Jim Champion; old bomb crater near Leaden Hall)

(Image: Jim Champion; old bomb crater near Leaden Hall)

Wandering the eerily peaceful heathland of the abandoned Ashley Walk Bombing Range today yields ominous clues to its former purpose. New Forest ponies drink from puddles collected in World War Two bomb craters and the remains of structures representing walls, ships and other air to ground targets are still visible amid the idyllic surroundings.

![New Forest ponies on Ashley Walk Bombing Range]() (Image: Jim Champion; New Forest ponies on former Ashley Walk Bombing Range)

(Image: Jim Champion; New Forest ponies on former Ashley Walk Bombing Range)

Line targets simulating railways were used to test attack techniques involving rockets and bombs. Wall targets, with their thick armour plating, helped evaluate Barnes Wallis’ now-famous bouncing bombs, including Highball and Upkeep. Other structures allowed for the testing of fragmentation bombs, and a number of aircraft pens were built to simulate those on Luftwaffe bases.

![abandoned rifle butts on Hampton Ridge in the Ashley Walk Bombing Range]() (Image: Jim Champion; abandoned rifle butts on the edge of Hampton Ridge)

(Image: Jim Champion; abandoned rifle butts on the edge of Hampton Ridge)

One giant structure that remains somewhat mysterious is a 79 by 70 foot slab of 6-ft-thick concrete called the Ministry of Home Security Target, more commonly known as the submarine pen. Local rumours suggest the sub pen was built to evaluate the best way for the RAF to destroy the heavily fortified German U-boat pens along the French coast. Tests revealed that 500 lb bombs were ineffective on the structure, and it wasn’t until the advent of earthquake bombs (cue the 12,000 lb Tallboy and the 22,000 lb Grand Slam) that German submarine pens could be penetrated. Other theories hold that it was built after the Battle of Britain to test improved air-raid shelters.

![Tallboy bomb crater on the abandoned abandoned Ashley Walk Bombing Range]() (Image: Mike Searle; Tallboy bomb crater on Ashley Walk Bombing Range)

(Image: Mike Searle; Tallboy bomb crater on Ashley Walk Bombing Range)

Inert Tallboys were the first earthquake bombs to be dropped on Ashley Walk range, followed by live versions soon after. The weapon would be employed to great effect by Nos. 9 and 617 squadrons against high profile targets including the Dortmund-Ems Canal, V2 rocket sites, the feared battleship Tirpitz and – of course – U-boat pens. Tallboy was even used to flatten Hitler’s holiday home, the Berghoff near Berchtesgaden, on April 25, 1945.

![Avro Lancaster bomber drops a Grand Slam earthquake bomb on the Arnsberg Viaduct in 1945]() (Image: RAF; a 617 Sqn Lancaster drops a Grand Slam on Germany’s Arnsberg viaduct)

(Image: RAF; a 617 Sqn Lancaster drops a Grand Slam on Germany’s Arnsberg viaduct)

But the biggest was yet to come. After a series of inert tests, Avro Lancaster PB592 dropped a live 22,000lb Grand Slam (aka Ten Ton Tess) from a height of 18,000 feet onto the range below. The bomb impacted near Pitts Wood and, after a nine second delay, blasted a massive crater 124 feet in diameter and 34 feet deep into the earth. Locals weren’t told of the test in advance! The next day, Lancaster PD112, flown by Squadron Leader C. C. Calder, successfully dropped its Grand Slam onto the Bielefeld viaduct in North-Rhine Westphalia, its earthquake effect causing 100 yards of bridge to collapse.

![Abandoned fragmentation target on the old Ashley Walk Bombing Range 2]() (Image: Mike Searle; remains of A & B fragmentation target)

(Image: Mike Searle; remains of A & B fragmentation target)

In January 2014, archaeologists began excavating the remains of the Ministry of Home Security Target on Ashley Walk Bombing Range, which was buried after World War Two ended, in a bid to discover whether any chambers survived inside, and what might be in them.

![Abandoned fragmentation target on the old Ashley Walk Bombing Range]() (Image: Mike Searle; remains of C & D fragmentation target)

(Image: Mike Searle; remains of C & D fragmentation target)

Archaeologist James Brown told the BBC: “There have been all sorts of rumours about things being buried inside; tanks, planes, bombs. We hear of that all over the forest.” He added: “Things that were once quite common, like pill boxes and airfields, there was a distinct attitude after the war to remove them, to forget almost. Now we’ve moved on 70 years or so, a lot of information is starting to disappear. What we get quite a lot across the forest is various lumps of concrete. We want to encourage people to realise it’s not a lump of rubbish that needs to be removed.”

![Grand Slam aka Ten Ton Tess bomb crater on the abandoned Ashley Walk Bombing Range]() (Image: Mike Searle; remains of Grand Slam bomb crater at Ashley Walk Bombing Range)

(Image: Mike Searle; remains of Grand Slam bomb crater at Ashley Walk Bombing Range)

Near the remnants of the submarine pens, the massive crater made by Ten Ton Tess has slowly disappeared into the heathland of the New Forest. The giant hole was largely filled in after the war, though its location remains barely visible to the discerning eye. As with other relics of the abandoned Ashley Walk Bombing Range, nature has been swift to reclaim the environment. But its compelling wartime history endures in the ruins left behind.

![Hidden history on the New Forests' abandoned Ashley Walk Bombing Range]() (Image: Martin Vaughan; the concrete arrow on Deadmans Hill once pointed towards targets on Leaden Hall)

(Image: Martin Vaughan; the concrete arrow on Deadmans Hill once pointed towards targets on Leaden Hall)

Related: The Wrecked Aircraft and Dummy Airfield of the Otterburn Ranges

The post Ashley Walk Bombing Range: Explore the Ruins of a Secret World War Two Test Site appeared first on Urban Ghosts Media.

(All images via Google Street View; former fighter revetments at RAF Harrowbeer)

(All images via Google Street View; former fighter revetments at RAF Harrowbeer)